Picture a cozy room in the heart of a Russian winter, snow blanketing the world outside. Inside, at the center of a family table, stands a gleaming metal urn, steam gently puffing from its chimney. This is the samovar—the traditional self-boiler that has shaped Russian tea culture for centuries. More than a tool to heat water, it has become a symbol of Russian hospitality, social customs, and daily life.

While many cultures have their own tea rituals, none have a relationship with drinking tea quite like Russia. Russians have historically embraced tea as a central part of their hospitality, developing unique customs and etiquette that set their tea traditions apart. The samovar transformed tea in Russia from just a drink into a cherished social ritual. Russian tea drinking is a slow, communal experience, marked by long conversations, bonding, and the use of traditional equipment that embodies the ritualistic nature of tea consumption in Russia. It dictated how tea was served, how guests gathered, and how Russian homes expressed warmth and community.

Let’s explore how this iconic metal container became the centerpiece of Russian tea tradition and a reflection of Russian culture.

The Origins of a Russian Tea Tradition

The story of Russian tea begins in the 17th century, when tea arrived as a diplomatic gift from Mongolian rulers. At first, it was a rare luxury, consumed only by the elite of tsarist Russia. Traditionally, tea was drunk in elaborate ceremonies by the nobility, while over time it became commonly enjoyed by merchants and peasants in more modest settings. Over time, trade flourished along the Great Tea Road, a caravan route that linked China and Russia. These tea caravans brought not only Chinese tea but also different varieties that appealed to the Russian market—from fragrant green tea to robust black tea.

Just as Chinese teas such as Longjing or Taiwan’s Dong Ding Oolong carry terroir and processing stories— influencing aroma, oxidation, leaf shape, and cup character — the teas imported into Russia also came with their own characteristics and required adaptation. The Russian palate favored strong, robust black teas. Over time, Russian merchants and tea traders selected teas suited to long transport, storage, and dilution — quite unlike the delicate green or oolong teas that thrive in more local, immediate consumption traditions.

As tea drinking spread across Russian households, the need for a more efficient brewing method grew. The traditional samovar, whose name literally means “self-brewer,” emerged as the perfect solution. By the 18th century, the city of Tula became the heart of samovar production. Known for its expert metalworkers, Tula turned the large metal container into both a household essential and a work of art.

In pre-revolutionary Russia, owning a samovar symbolized not only comfort but also social standing. Whether in a merchant’s house in St. Petersburg, a peasant cottage, or a noble estate, the samovar represented the shared rhythm of Russian life—slow, warm, and centered around tea.

How the Traditional Samovar Works: Function and Form

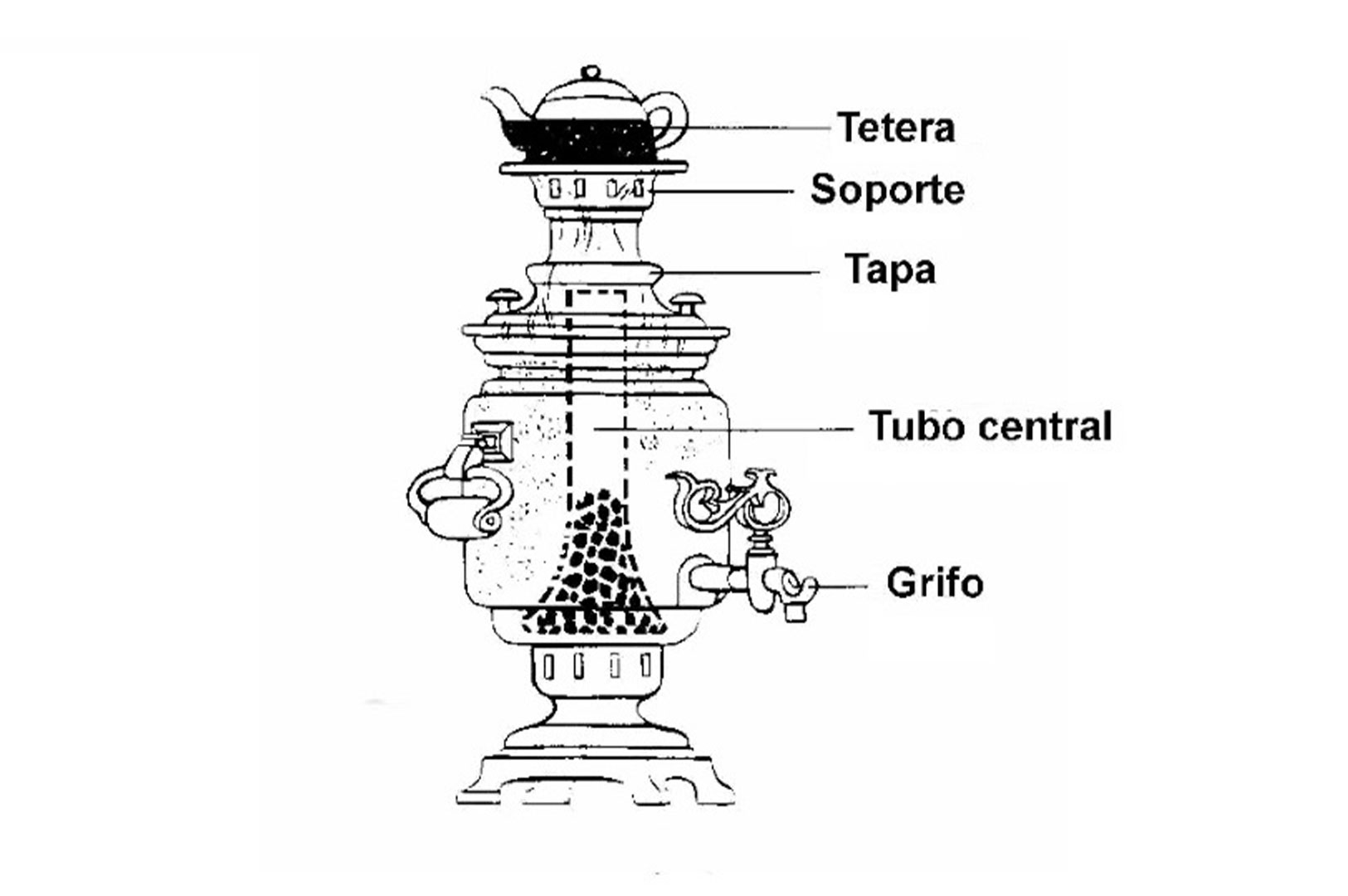

To appreciate Russian tea culture, one must understand how a traditional samovar consists of several ingenious parts:

- The Body (Korpus): A large metal container that holds hot water.

- The Central Pipe (Truba): A vertical tube in the middle where charcoal, pinecones, or wood burns to heat water.

- The Spigot (Kranik): A small tap at the base that dispenses boiling water.

- The Teapot Stand (Konforka): The top surface that supports a small teapot, known as the zavarnik.

This efficient design not only kept water at the right temperature for hours but also produced gentle warmth that filled the room. The traditional samovar became the soul of Russian homes, allowing tea to be served continuously throughout the day—a symbol of ever-present Russian hospitality.

The Russian Tea Ceremony: Zavarka and the Art of Drinking Tea

The Russian tea ceremony differs from the formalized practices of Chinese tea or Japanese matcha rituals. In Russia tea culture, drinking tea is informal yet deeply meaningful. It’s not just a drink—it’s an experience shared among family and friends.

The Art of Zavarka

The samovar made possible the creation of zavarka, a concentrated form of black tea brewed in the small teapot resting atop the samovar. A small quantity of loose leaf tea is steeped in boiling water, forming a strong, almost syrupy concentrated tea.

Each guest personalizes their cup:

- Pour a bit of zavarka into a glass or metal holder.

- Dilute it with hot water from the samovar’s spigot.

This ritual reflects the Russian tradition of individuality within community. Some prefer strong tea, others milder; some add herbs, dried fruits, or even fruit preserves. In Russian households, tea is typically served with sugar cubes, spiced cookies, or sweet pastries—often laid out on a lace tablecloth with matching saucers and ornate tea sets.

The Role of Food: Traditional Accompaniments to Russian Tea

The story of Russian tea begins in the 17th century, when tea arrived as a diplomatic gift from Mongolian rulers. At first, it was a rare luxury, consumed only by the elite of tsarist Russia. Traditionally, tea was drunk in elaborate ceremonies by the nobility, while over time it became commonly enjoyed by merchants and peasants in more modest settings. Over time, trade flourished along the Great Tea Road, a caravan route that linked China and Russia. These tea caravans brought not only Chinese tea but also different varieties that appealed to the Russian market—from fragrant green tea to robust black tea.

As tea drinking spread across Russian households, the need for a more efficient brewing method grew. The traditional samovar, whose name literally means “self-brewer,” emerged as the perfect solution. By the 18th century, the city of Tula became the heart of samovar production. Known for its expert metalworkers, Tula turned the large metal container into both a household essential and a work of art.

In pre-revolutionary Russia, owning a samovar symbolized not only comfort but also social standing. Whether in a merchant’s house in St. Petersburg, a peasant cottage, or a noble estate, the samovar represented the shared rhythm of Russian life—slow, warm, and centered around tea.

More Than Just a Drink: The Samovar as a Symbol of Russian Hospitality

In Russian tea culture, drinking tea around a samovar was never only about the drink itself. It was about connection. To serve tea was to show care and respect.

- A Symbol of Welcome: Keeping a samovar constantly running was a hallmark of Russian hospitality. Guests were always offered more tea—a small gesture with great warmth.

- The Great Equalizer: Whether in pre-revolutionary Russia or during the soviet era, drinking tea around a samovar united people of all backgrounds.

- An Integral Part of Russian Life: The samovar provided not only hot water for tea but also for washing and cooking. It was an integral part of daily life and family routines.

The phrase “to sit by the samovar” became synonymous with comfort, conversation, and togetherness. It was during tea time that families shared stories, friends discussed politics, and generations bonded—often sipping tea late into the night.

The Samovar in Russian Art, Literature, and Culture

From Russian art to literature, the samovar became an enduring emblem of Russian culture. Writers such as Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Dostoevsky often used tea parties and samovar scenes to reflect domestic harmony or tension. Paintings from the Russian empire era often depict a merchant’s wife seated near a samovar, surrounded by family, tea served in ornate glasses, and fruit preserves glistening nearby.

In this way, the samovar transcended function—it became an artistic and cultural motif, representing warmth, tradition, and Russian life itself.

The Soviet Era and Beyond: The Evolution of Russia’s Self-Brewer

During the soviet era, the samovar adapted to modernity. The charcoal-based self brewer gave way to electric models, keeping the traditional samovar shape but simplifying its operation. Families across Russia could still enjoy tea time without tending to coals.

Even today, Russian homes often display a samovar—sometimes an heirloom from grandparents, sometimes a decorative centerpiece. At dachas (country houses), families still light traditional samovars, enjoying the nostalgic scent of smoke and the unique flavor of tea brewed over live fire.

The Enduring Legacy of Russian Tea Culture

Few national customs reflect warmth and unity like tea in Russia. While Chinese tea is rooted in ceremony and British tea emphasizes formality, Russian tea tradition centers on hospitality, flexibility, and community.

The samovar turned drinking tea into an act of belonging. It connected generations, welcomed strangers, and filled homes with the comforting aroma of tea leaves and burning pinecones. Whether it’s black tea, green tea, or blends enhanced with add herbs and dried fruits, tea production remains a thriving part of Russia's heritage.

To understand the samovar is to glimpse the Russian soul: resilient, warm, and deeply communal. Every cup poured from a samovar carries centuries of Russian tradition, hospitality, and heart.

So the next time you see this shining metal container with its graceful spout and small teapot perched on top, remember—it’s not just a drink. It’s the essence of Russian culture: a gathering, a story, and a shared warmth that endures through the ages.

Loose Tea Leaves: Elevate Your Singapore Tea Experience

In a city that moves as fast as Singapore, the simple act of brewing a cup of tea can feel like a small rebellion—a moment of intentional calm. More and more tea lovers are discovering that this moment is profoundly elevated when they make the switch from conventional tea bags to loose tea leaves. This…

Tea Leaf Singapore: An Exquisite Journey of Flavours, Traditions, and Moments

Singapore’s strategic position as a maritime trading hub has nurtured a rich tea culture where ancient traditions blend with modern innovation. The local love for tea runs deep, shaping Singapore’s unique tea culture and fostering a strong appreciation for every cup. Singapore continues to honor its tea traditions while embracing new innovations, ensuring that the…

Korean Barley Tea: A Journey into Boricha and Its Rich Traditions

Walk into any Korean restaurant, and before you glance at the menu, a glass of amber-colored boricha (보리차) arrives. This Korean barley tea is as fundamental as water in Korean culture—served hot or cold, a staple in everyday life and a gesture of hospitality. While roasted barley tea is popular across many East Asian countries,…

Mugicha Barley Tea: Japan’s Beloved Caffeine-Free Summer Drink Unveiled

Long before green tea became Japan’s iconic beverage, mugicha barley tea—a golden, nutty roasted barley tea—has refreshed Japanese families for centuries. Unlike traditional tea from Camellia sinensis leaves, mugicha is a naturally caffeine free herbal tea made by steeping roasted barley grains in hot water. This traditional barley tea has evolved from an imperial luxury…

Buckwheat Tea Unveiled: Singapore’s Rising Caffeine-Free Wellness Beverage

Singapore’s health-conscious community is embracing buckwheat tea, a caffeine free tea known for its rich cultural heritage, unique nutty flavor, and impressive health benefits. This traditional Asian beverage, also called soba cha in Japan, offers a soothing alternative to green tea or coffee, perfect for Singapore’s tropical climate and wellness goals. Its growing popularity reflects…

Japanese Green Tea from Japan: Unlocking the Secrets of Authentic Varieties and Brewing

Experience the rich tradition of authentic japanese green tea from japan, a beverage refined over centuries with unique steaming methods that preserve its vibrant color, rich aroma, and delicate taste. This comprehensive guide introduces you to Japan’s most treasured green tea varieties, their extensive health benefits, and how to enjoy japanese tea perfectly brewed, whether…

How to Make Matcha Latte: A Step-by-Step Recipe Quest

There’s a special kind of satisfaction that comes from mastering your favorite café drink at home. When it comes to the vibrant and creamy matcha latte, the rewards are particularly sweet. Learning how to make matcha latte in your own kitchen not only saves you money but also gives you complete control over the quality,…

Mastering the Art of Matcha Green Tea Latte Recipe: Your Path to Perfection

There’s a unique kind of magic in crafting your own café-quality matcha green tea latte at home. It’s the satisfaction of watching vibrant green matcha swirl into creamy, frothed milk, the joy of customizing it to your exact taste, and the simple pleasure of sipping a wholesome, delicious beverage you made yourself. Beyond the significant…

Afternoon Tea in Singapore: Your Passport to Tradition and Modern Fusion

Imagine the gentle clink of fine china, the sight of a beautiful three-tiered stand laden with exquisite sweet and savoury treats, and the aroma of freshly brewed tea filling the air. This is the timeless allure of afternoon tea in Singapore, a ritual that feels both wonderfully indulgent and deeply comforting. In a city that…

Discover the Rich Flavors of Ceylonese Tea: A Complete Overview

Picture a landscape of rolling hills carpeted in a sea of green, where misty clouds kiss the mountaintops and the air is crisp and cool. This is the heartland of Sri Lanka, the island nation once known as Ceylon, and the origin of one of the world’s most celebrated teas. For over a century, the…